Pennsylvania Stereograph: The Industrial & Domestic

by Ally Kotarsky

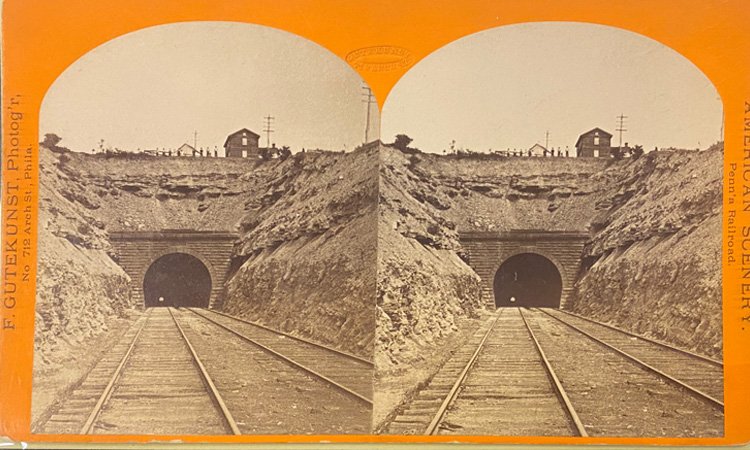

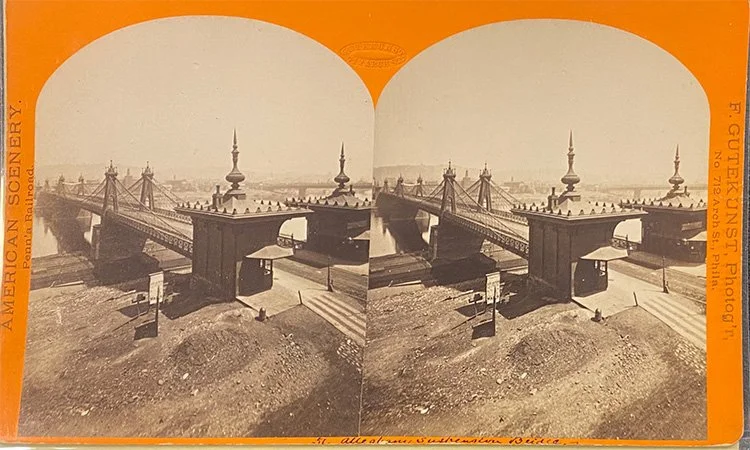

In 1875 Philadelphia-based celebrity and Civil War photographer Frederick Gutekunst was sent traveling along the recently expanded Pennsylvania Railroad to capture the landscape and scenery along the way. A collection of over 240 stereographic images from the Philadelphia, middle, and Pittsburgh regions of the state resulted. Of these 240 images, 142 of them have been collected by the Library Company of Philadelphia. Within the series, viewers can see the railroad, workers, train cars, tunnels, bridges, and natural scenery captured by the early three-dimensional technology that stereo photography could offer. After viewing the full collection that the Library Company had of this survey of the Pennsylvania Railroad, these two images stood out as two of the most industrial images in the collection. In contrast, many of the other images were more natural landscapes, featuring hills, trees, and ravines, with the only human intervention being the railroad itself, and potentially a train station or other small building construction along the way. Growing up in a lineage of steel and factory workers, the lines between industrial and domestic have always been blurred within my own understanding of home and memory. In some ways, these two stereographs speak to the same blurring of lines, as the viewer has a very solitary experience in the consumption of these images, as well as how much they were reproduced and distributed amongst individuals and collected into their homes and personal archives, while the images themselves are of large-scale human interventions driven by the industry of the region.

LABEL

This stereograph card was taken by Civil War and celebrity photographer Frederick Gutekunst during his 1875 government-funded expedition of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The stereographic image utilized the space between our eyes to create the illusion of a three-dimensional image when viewed through a stereoscope. They were produced and multiples, and collected by private and public institutions, as well as individual families. The tunnel shown in this image was carved through the Allegheny Mountains and is now known as part of the historic Gallitzin Tunnels in Cambria County, Pennsylvania.

COUNTERLABEL

By the time Frederick Gutekunst struck out to document the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1875, stereograph images had become so popular that they began to simulate an experience equal to physically traveling to a new place. Americans were able to experience westward expansion as it happened through the low-cost collection of these cards. The mass distribution of three-dimensional space essentially allowed for the possession and archiving of the American West and beyond. While many of the cards in Gutekunst’s collection seem to focus on the landscape of Pennsylvania, the series is a reference to the (white) man’s ability to traverse and dominate the wild landscape between the two production hubs of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. This card showcases the great lengths and feats of construction man was willing to go to in order to conquer the landscape and all of the life that it held by boring directly through mountains.

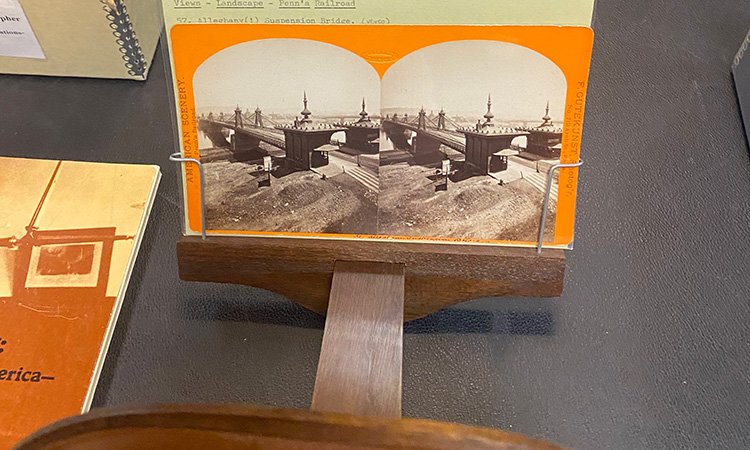

When holding these cards, these massive industrial structures are miniaturized. While the image is repeated for the stereograph effect, each photograph is only a couple of inches wide, and the card itself is made of cardboard only about an 8th of an inch thick. The structures can be stacked amongst other numerous images and stored within one’s home archive, in a photo album, or even just a shoebox under the bed. What could it mean to the Pennsylvania family who would collect this image, and how could the three-dimension space of this colossal structure be experienced in a family home?

In my research of these images I am reminded of Susan Stewart’s writing on the miniature and gigantic in her book On Longing. she writes “we are able to hold the miniature object within our hand, but our hand is no longer in proportion with its world. Instead, our hand becomes a form of undifferentiated landscape, the body in a kind of background,” and in contrast, “the gigantic becomes an explanation for the environment, a figure on the interface between the natural and the human. Hence our words for the landscape are often projections of an enormous body upon it, the mouth of a river, the foothills fingers of the lake, the heartland, the elbow of the stream.”

Viewing a stereograph image is an embodied process. As you hold the stereoscope to your face and focus on the image, the environment you are physically in fades away. Finally, when held correctly, only the three-dimensional photographic image is visible. This all-encompassing view may not be that impressive to someone in 2023, where virtual reality and AI have infiltrated almost any aspect of the physical experience we could desire, but for someone in the 19th century, this full-body experience would be an entirely new way to the miniature expanding into the gigantic, and the industrial entering the intimacy of their home. As the Allegheny Suspension Bridge and Tunnel were viewed, it's possible that one would still hear the voices of their loved ones in the room the wringing out of household linens, or the crackle of the fireplace while their body is brought into the gigantic world of the industrial expansion.

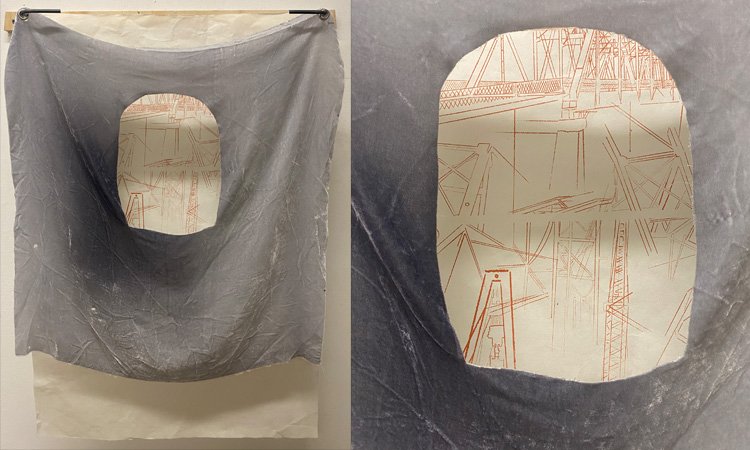

Inspired by these images, I have created a print of the Donora-Webster Bridge. This bridge was built at the head of the 20th century for southern Pennsylvania rail traffic and was later converted to automobile usage before being declared a structural loss and demolished by the Pennsylvania government in 2015. This bridge has long represented the bleed between industry and home for me, as a descendant of Donora. The print captures the completion and demolition, and only a small portion of the bridge can be viewed through the soft velvet portal. The closer the viewer gets to the portal the more of the full print can be viewed, and as the viewer gets closer, the velvet is removed from their periphery. I am hopeful that the velvet will reference preciousness, like a reliquary or keepsake, and the steel rod that supports it brings the material straight through that.