After Hours

A Celebration of Technical and Creative Mastery

The Stella Elkins Tyler Gallery at Tyler School of Art and Architecture presents After Hours, an exhibition that flips the script on who gets the spotlight. The attention turns to the artistic practices of Tyler’s studio technicians—the very people who keep the studios running—this show proves that those behind the scenes are also making waves in the creative world. With works spanning ceramics, fibers, printmaking, sculpture, and digital fabrication, After Hours is a testament to both technical mastery and artistic vision. This show exposes the seamless fusion of skill and imagination, proving that the hands that sustain an artistic community are often the same ones shaping its future.

Meet the Technicians

lydon frank lettuce

Hailing from rural Pennsylvania, lydon frank lettuce crafts an interdisciplinary practice that interrogates language, social structures, and desire. Combining performance, psycholinguistics, and embodied writing, their work challenges systems of power while embracing the playful and the profound. Holding an MFA from California Institute of the Arts and a BFA from Parsons, lettuce’s work is an intellectually charged exploration of language and identity.

Brad Lunsford

Philadelphia-based craftsperson Brad Lunsford bridges the gap between computer-aided design and traditional metalworking, crafting intricate sound-making objects that transform materiality into immersive sensory experiences. His process, documented through sound recordings and audio collage, layers sonic and visual narratives that challenge the boundaries of form and function.

Katie Kaplan

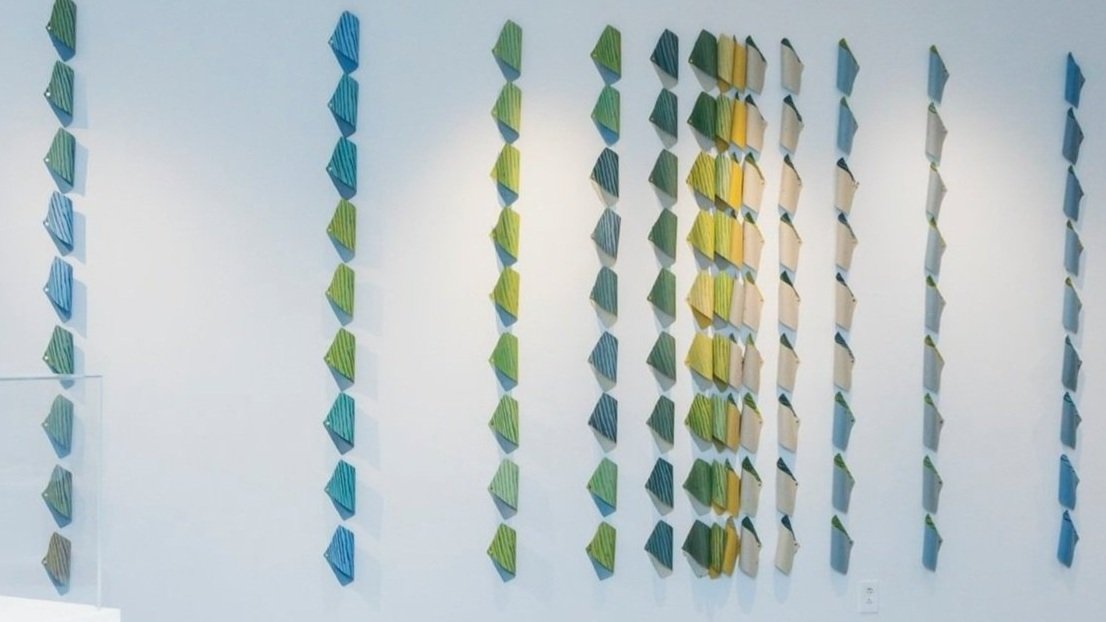

Blurring the boundaries between printmaking, sculpture, video, and installation, Katie Kaplan infuses her multidisciplinary practice with ecological and social concerns. A Pratt Institute graduate and Tyler’s Fibers and Material Studies Studio Technician, Kaplan cultivates a natural dye garden that seamlessly merges sustainability with art-making. Her work has been featured in residencies and fellowships nationwide, marking her as a pivotal voice in fiber arts.

Andrew Mahaffie

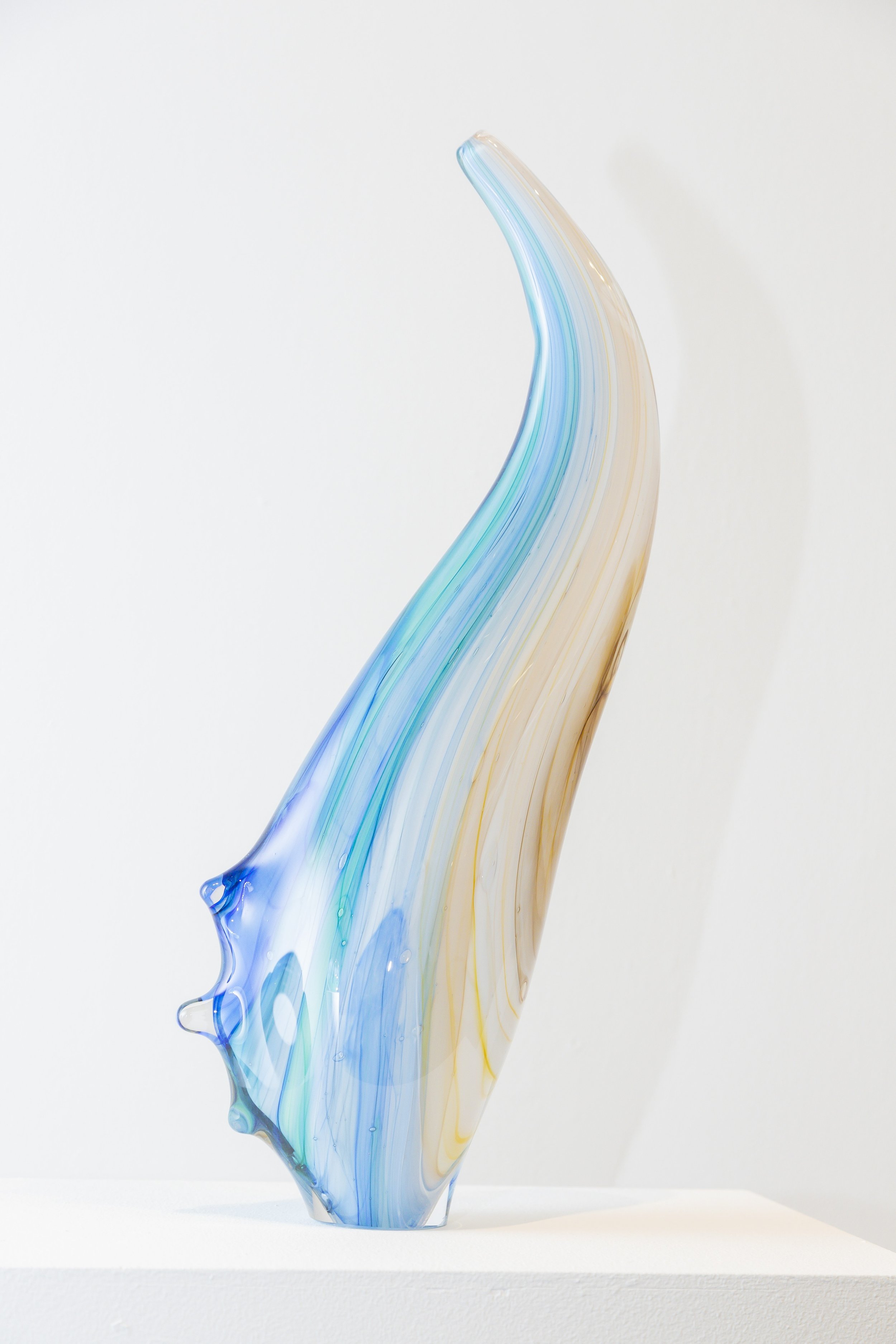

Glass artist Andrew Mahaffie embraces both tradition and play in his approach to sculpting, casting, and coldworking. Originally from Washington, D.C., and trained under Gene Koss at Tulane University, Mahaffie revels in the fluidity of glass, pushing the limits of the medium to explore its dynamic and ever-changing form.

Dawn Simmons

Since joining Tyler’s community in 2006, printmaker Dawn M. Simmons has not only championed safer studio methods but has also cultivated a practice that balances technical expertise with deep historical engagement. With an MFA from the University of Michigan and studies in Japan as a Monbusho Scholar, she reimagines print media with a blend of tradition and innovation.

Feather Chiaverini

Feather Chiaverini, a fiber and performance artist, stitches together textile traditions with contemporary discourse. As Residency Director of the Queer Materials Lab, their work is deeply rooted in identity politics and experimental material processes. Featured in spaces such as Temple Contemporary and ROY G BIV Gallery, Chiaverini’s installations bridge the gap between academic inquiry and community engagement.

Ceramicist Donte J. Moore delves into the intersection of humanity and mechanization, examining how industrialization shapes identity through his sculptural forms. With an MFA from the University of Delaware, his work—exhibited nationally and internationally—grapples with the emotional and existential weight of manufactured environments, bridging personal and collective narratives through clay.

Donte J. Moore

Kedrick McKenzie

With an MFA in Ceramics from Tyler and a BFA in Spatial Arts from San José State University, Kedrick McKenzie crafts narratives of history, identity, and place. His research-driven practice critiques consumer culture while integrating craft traditions and ephemeral materials, reimagining historical narratives and notions of home with sensitivity and precision.

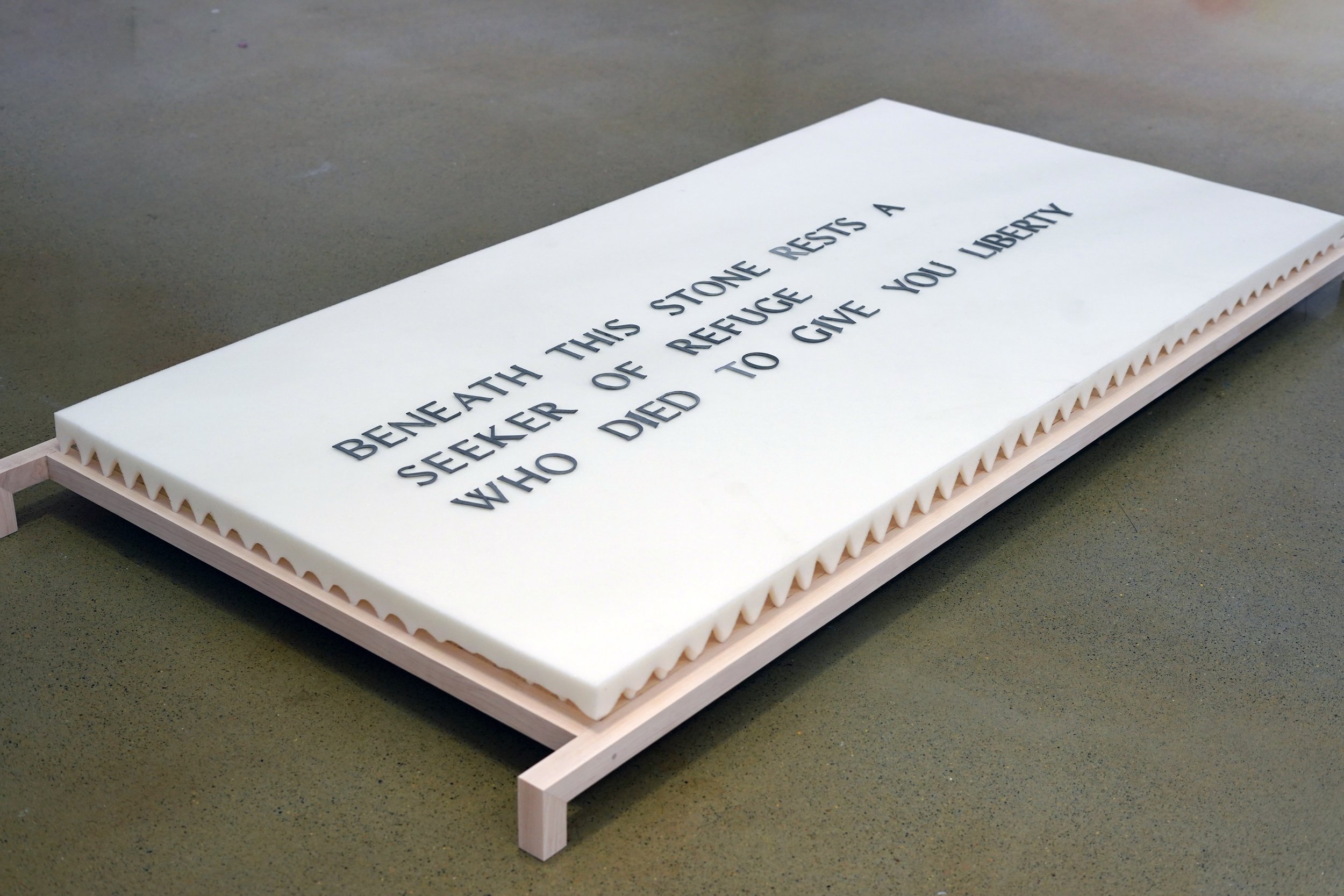

Paolo Mentasti

Sculptor Paolo Mentasti, originally from South America, excavates contemporary life through the lens of archaeology. With a BFA from The Cooper Union and an MFA from Tyler, Mentasti fabricates fictional artifacts that blur the line between history, memory, and speculative futures. Utilizing ceramics and archival materials, he constructs anachronistic records that challenge our understanding of time and place.

Powered by the exhibition, immersive programming, ands dynamic discussions, students, faculty, and staff had the chance to step behind the scenes and uncover the creative processes and ideas that drive these artists' work.

Katie Kaplan talks about her experience as a technician and an artist and how they can influence each other. "As the Fibers technician, I experience so much play between my professional labor and my studio practice, with new insights in one area often informing the other. For example, I might be teaching a student a certain technique and feel a spark towards a new direction I want to explore in my work. This is especially true for me as a maker—an artist who often works through concepts through tactile and visual experimentation. Likewise, all the pieces I have on view in the exhibition are a result of the fluency of technical skill that is required for me to do my job."

On Friday, February 7, the audience was ready, but due to illness the first event had to be rescheduled and Experiments Firing Ceramics with Hot Glass will take place on Friday, February 14, at 2 PM in the Tyler Glass Studio.

I had the privilege of catching a glimpse of the excitement during a few of the extensive hours that artists Andrew Mahaffie and Donte J. Moore have dedicated to preparing for this event. This demonstration will unveil their ongoing research exploring the intersection of ceramics and glass. During this time they pushed the limits of traditional ceramic firing techniques, harnessing molten glass as an alternative heat source in a high-stakes experiment with ceramics. Employing a modified saggar method—typically used to create rich, atmospheric effects on clay—they introduced an element of unpredictability, allowing natural materials and raw fire to dictate the final surface of their forms. The result was an ephemeral dance between elements: earth meeting fire, solid encountering liquid, form becoming flux.

As the passers by gathered around the blazing crucible of their process, the boundaries between disciplines dissolved. Glass and clay, often treated as distinct entities in the realm of craft, became interdependent—one sustaining the transformation of the other.

Reflecting on his role, Mahaffie notes, "All of the technicians are stewards of their respective studios. We maintain an active knowledge of the spaces and build relationships with all of the tools, equipment, and people that pass through them. Being practicing artists in the studios we are charged with, builds the strongest possible form of this knowledge as we are interacting with the space in the same way as a student or faculty might. We rely on our studios as a conduit to channel our creative energies just as much as the studios rely on our labor to continue operating.

The objects in this show to me are that two-way street made physical, our labor as technicians is a benefit to the university and its students but also allows us to develop and maintain an important resource to ourselves as artists. The more we make our own work out of the studio, the greater our connection to the space and its needs will be."

The demonstration did not merely display technique; it illuminated the physical and conceptual alchemy that underpins material-based practices. The immediacy of the moment—the hiss of steam, the glow of molten glass, the crackle of heat meeting clay—brought an undeniable energy to the room. Here, experimentation was not an abstract concept; it was alive, unfolding in real-time, demanding the attention of both artist and observer.

If Experiments Firing Ceramics with Hot Glass celebrated the visceral beauty of process, TECHTalk shifted the focus to the unseen: the labor, expertise, and embodied knowledge of technicians who sustain the machinery of art institutions. On Friday, February 7, in the Stella Elkins Tyler Gallery, artists Paolo Mentasti, lydon frank lettuce, and Kedrick McKenzie took center stage, not just as facilitators of others’ work, but as artists, thinkers, and essential forces within the Tyler ecosystem.

Paolo Mentasti opened the discussion by exploring the relationship between political borders, time, and abstraction, reflecting on how landscapes shape artistic expression. He drew connections between sundials and shifting borders, noting how both measure and define space yet remain subject to change. Material and scale play a crucial role in his work: "Change the scale, and you change the perception," he remarked, emphasizing how his sculptural forms morph under different spatial conditions. Mentasti also discussed how landscapes and architecture inform his creative process, integrating personal memories into his artistic practice. Themes of control over nature and material evolution emerged in his work, particularly in his reflections on erasure and remembrance. When he first arrived in Philadelphia, he was puzzled by the collective urgency to kill the spotted lanternfly. "This invasive species had found a home, yet it was destined to be erased," he noted. This idea resonated with his ongoing exploration of how we document, preserve, or erase histories—both personal and collective—driving his desire to leave a record behind.

Kedrick McKenzie reflected on California’s industrial and agricultural past, noting, "California has always been a place of reinvention, but also of forgotten histories." He explored themes of labor, material culture, and history, considering how these forces shape both the built environment and personal narratives. He spoke about the significance of a photograph capturing his earliest act of making with his siblings, a moment that, for him, embodies the deep connections between memory, craft, and familial ties. This notion of nostalgia extends into his fascination with Fiesta ware, a mass-produced yet highly collectible ceramic line, whose vibrant colors and streamlined forms tie into broader histories of labor, design, and modernism. He discussed the influence of Spanish architecture and its intersections with craft traditions, emphasizing how these stylistic elements contribute to his understanding of materiality and space.

But beyond aesthetics, McKenzie is captivated by how objects tell their own stories over time. "It’s that experience of artifacts showing their material history that fascinates me. I think a lot about cleanliness and straightforwardness in design—how functional objects can be subverted through material choices, how something meant to be useful can become something else entirely." This transformation of the everyday into something unexpected remained central to his perspective, as he reflected on the ways in which ordinary items accumulate meaning over time. And while his artistic inquiry often looks backward, he wrapped up with a more lighthearted nod to his present: "None of this would be possible without my dog, Cheese."

lydon frank lettuce, on the other hand, introduced an alternative approach through performance and live writing. "Writing is both a muscle and an excavation—carving into the world through words," they explained. Their practice revolves around play, PLEASURE, and language, seeking to challenge social expectations and redefine identity through performative gestures.

Through their various personas—such as Dr. Seymour Vile—they critique and reimagine social constructs, using exaggerated gestures and theatricality to disrupt norms.

"Performance can be very scary, but so important," they remarked, highlighting the role of discomfort and pleasure in their work. As a queer student, they lacked access to comprehensive sex education—something Dr. Seymour Vile now seeks to provide.

"I feel like I’m constantly confronting false binaries—whether in gender, power, or expression," lettuce reflected. Dr. Vile’s passionately detailed and earnest exploration of quantum physics, galactic collisions, and, most importantly, black holes, seamlessly sets up a powerful metaphor: just as a black hole is at the center of every galaxy, the anus is central to the galaxy of inclusive pleasure education.

Whether wrestling through words and dirt, reimagining identity and fluidity in an ever-shifting exploration that destabilizes fixed roles, or performing an isolated game of tennis in the gallery—evoking repetition, solitude, and echoes of past pleasures—lydon grapples with identity, pleasure, and play, turning the world on its head.

Technicians are the architects of possibility, ensuring that students’ and faculty members’ visions materialize. The panelists spoke candidly about the duality of their roles—both indispensable and, at times, invisible. They dissected the physical and intellectual demands of their work, offering insight into the depth of knowledge that resides in technical labor. Through images, performance and candid talks, the gallery came alive.

Beyond personal anecdotes, the conversation tapped into larger currents—questions of artistic hierarchy, labor precarity, and the undervaluation of craft in contemporary discourse. The discussion did not dwell in abstraction; it carried weight, resonating with an audience deeply embedded in the institutional dynamics of art education. By the end of the session, one thing was clear: this was not simply a panel. It was a declaration. A call to recognize, to reframe, to reimagine the role of technicians as both makers and intellectual contributors to the field.

What remains, long after the fire has cooled and the panel has ended, is a new awareness—of material, of process, of the hands that build the foundation upon which art stands. More than just an exhibition, After Hours is an invitation—an opportunity to appreciate the depth of talent within Tyler’s studio technician community and to rethink how we define artistic labor in academia. It’s a celebration of craftsmanship, curiosity, and the creative spark that persists long after the workday ends.

Photo Credits: Kait Schnorbus

Essay written by: Erin Boyle