Izzy Coopersmith

Ephemeral Nature of Environmental Art: Collision of Permanence and Value

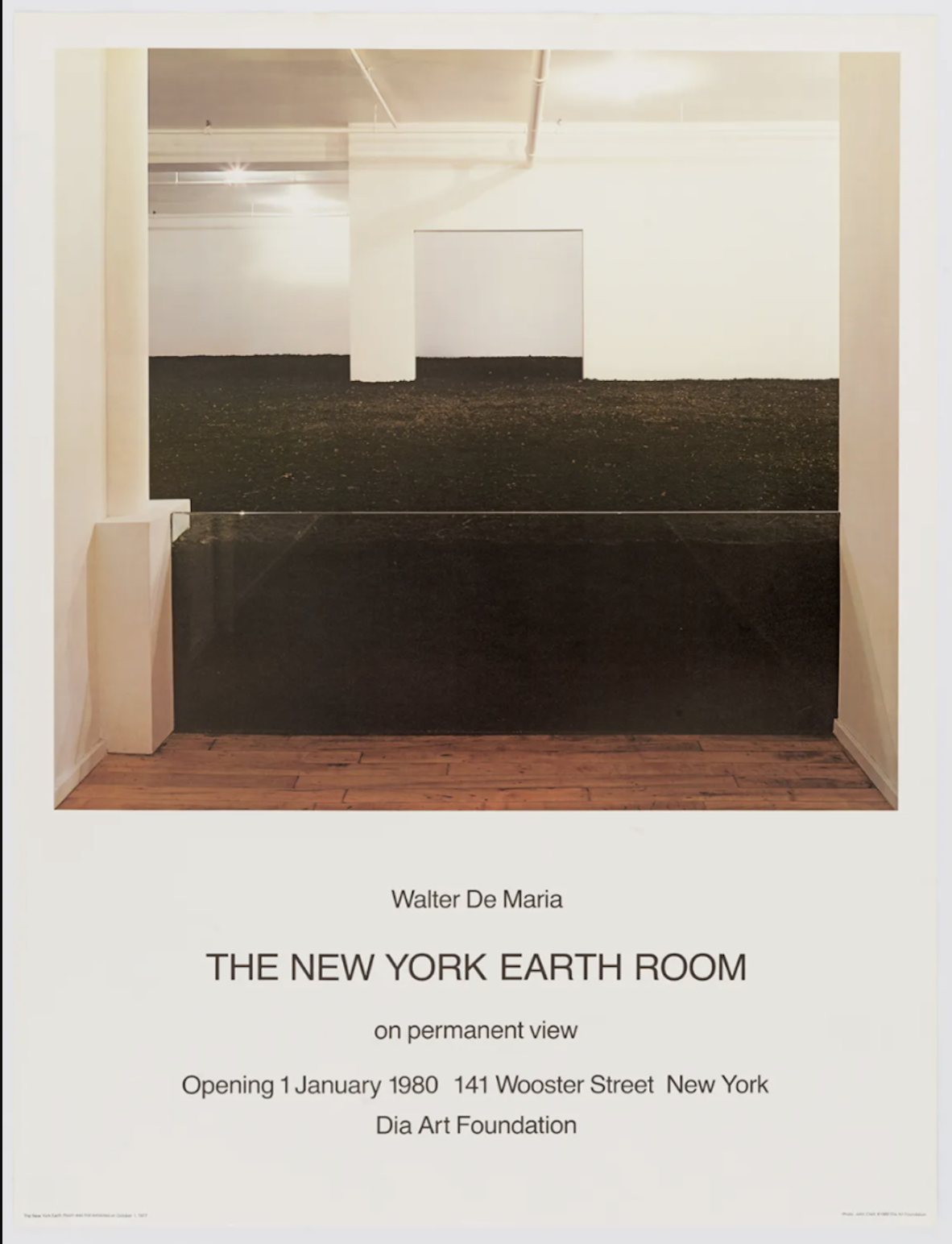

Walter de Maria (1935-2013), The New York Earth Room, 1977 Poster for the 1980 reopening of Walter De Maria, Dia Art Foundation. ©Estate of Walter De Maria/Walter De Maria Archive.In looking at the relationship between preservation and the intentions of environmental land art, one usually ends up overriding the other. The art world tends to value permanence over temporary works, literally and figuratively, and when permanence is not feasible, environmental art is pushed to the side. How does this relationship change when money, intentional decay, and preserved material come into the equation? The professional art world does not always know how to handle environmental works that decay, move, and change over time and the intention of the artist is more than often disrupted.

Walter de Maria’s Earth Room became a permanent installation at the Dia Art Foundation in 1980. In its minimalist nature, it is made of topsoil and dirt, and the only things needed to create the room are material and space. The soil alone omits moisture which allows mold and mushrooms to appear so the foundation has closed the room many times for conservation purposes. More recently, they added an HVAC unit to prevent such things from interfering with space. The environment of the room has changed completely: how the soil interacts with the air, the sound of the room, and how visitors feel entering the space. Without the moisture, the air has become thinner and the soil has lost the smell of the earth that would once strike the viewer as soon as they walked into the room. The work was intended to be “pure dirt” and in its ‘preservation’, the ethos of the piece has been changed entirely, becoming a sterile version of what it once was. In taking away the ephemeral qualities of environmental art, one takes away the characteristics of the environment itself.

Beverly Buchanan (1940-2015), Marsh Ruins, 1981 ©Amelia Groom, 2019Some land art is made with the intention of decaying over time. Hidden in the Marshes of Glynn in Brunswick, Georgia, three unmarked stones made of concrete and tabby are slowly being swallowed up by the land, as they were designed to be. Placed in 1981, these stones are Beverly Buchanan's Marsh Ruins. The word ‘ruins’ is in the name of the piece so deterioration and breakdown are invited processes. The mix of concrete and tabby, which is made up of lime, sand, and oyster shells, is a material historically used as grave markers by the black community during enslavement. The allowance for the decay holds a strong message for life and death. When they were installed, the future of the rocks were not a part of their plan. Over time, the tide and weather has eroded the concrete away, so much so that Buchanan thought they might need attention but deliberately let them be. With no preservative actions, the environmental artwork is allowed to interact with the environment as it was intended to.

Mary Miss (May 27, 1944), Greenwood Pond: Double Site, 1989-1996, © Mary Miss Des Moines Art Center commissioned Greenwood Pond: Double Site in 1989 by female land artist Mary Miss who completed the work in 1996. It was installed in the site and was intended to be a part of the center’s permanent collection after they pledged to maintain the project. Miss worked with groups of scientists, botanists, and the Native American people of the area to restore the wetlands and create a space for people to interact with the environment directly. Made from wood, metal, steel, stone, and other mediums, the walkways provide an invitation for the patron to admire the nature they are in and the human world around it. As an outdoor installation, the conditions of Double Site are more unpredictable than other works which is why the maintenance of this work is a crucial aspect. Unfortunately, the Des Moines Art Center has not been able to keep up with the upkeep and have decided to take down the piece entirely as it would be too expensive to repair as of January 2024. The response from the community is extreme disappointment and Miss herself offered solutions to the DMAC that involved an intervalled conservation with cheaper materials but they said it was ‘not feasible.’ It is an ironic turn of events that a site-specific installation made for ecological awareness has to be taken down due to the museum's inability to keep up with its environment.

Christo (1935-2020) and Jeanne-Claude (1935-2009), The Wall - Wrapped Roman Wall, 1973-1974, PhotolithographThe artists Christo and Jean-Claude were known for their grand public installations with extremely limited life spans. Left over from these events are the preliminary drawings and the official photographs. Here is an example of one of the larger projects which is part of a series of wrapped monuments from around the world to symbolize the preservation of history and the significance these structures hold in daily lives. Often with years of planning, the projects would only be up for a few weeks. This image here is an official hand-signed photograph of the Roman Wall, wrapped in 1974. The photo is 19x27in and is currently being sold for €2400 (about $2600) on Artsy.net. On the same site, these photographs ranged between €1500 ($1700) and €9000 ($9700). With an artwork that is purely temporary, as land art is more often than not, it is interesting to look at an example where the permanent evidence is highly valued.

Femke van Gemert is a Dutch artist who uses completely recycled textiles in her work dedicated to bringing awareness about the environmental crisis and anthropocene. The tapestry pictured was made in 2021 and titled Land & Water II which calls to the earth as it was before, during, and after humans, creating an “everlasting state of earth and water.” In using a material that is creating a lot of waste, the cause of many environmental issues, the textiles bring up this idea of permanence - as if the only way to dispose of them is to reuse them until they decompose. Gemert is very aware of the breakdown of organic materials and aims to show that materials will show their wear by changing over time.

Femke Van Gemert, Land & Water II, 2021 Recycled Textiles, 150 x 183 x 10 cm ©Femke Van GemertIzzy Coopersmith

(she/her)

Art History ‘24

Hi! My name is Izzy Coopersmith and I am a junior Art History major with a minor in Art expected to graduate in Spring 2025. I am very excited to present my research on land art! My special interests include environmental art, feminist theory, and material studies. I am also fascinated by surrealist paintings, Northern Renaissance prints, and every type of fiber art imaginable. I love to write, knit, read, garden, hike with my dog, and sit with my cat.

Instagram: @isabelawolfart