Folk, Factories & Fiddles: Sheet Music as Cultural Record of the Wissahickon Valley

by Marie Latham

Sheet music can play many functions in preserving history. It acts as a record of tunes, first and foremost, intended to be read and repeated by many in the future. There was an explosion of sheet music preserved in Reconstruction America with beautiful cover illustrations, including this Wissahickon Polka, printed in 1858.

The proliferation of the use of lithography in the U.S. in the mid-19th Century dramatically changed the world of popular visual art. The process could cheaply and easily produce multiple high-quality copies of an image. Covers of sheet music were now alive with an odd partnership of musical composition and advertising; a spontaneous record of the contemporary streetscape. They often idealized the city and its industries, including its surrounding landscape.

And Philadelphia had an environment ripe for these visual daydreams of pastoral life. A century ago, when most of America was rural, the Wissahickon region directly west of the city buzzed with industrial development via watermills. In 1868, in line with the rise of transcendental thinking surrounding the protection of natural beauty, the Fairmount Park Commission acquired the Wissahickon Valley land and demolished most of the industrial infrastructure.

In this way, it is similar to the cultural history of the polka dance itself, originating as a folk dance in Bohemia beloved by agricultural working populations. The polka invaded Paris and London ballrooms in 1844 and “polkamania” swept Philadelphia that same year, transforming the dance into a social status symbol far from its humble origins. The cover of the Wissahickon Valley Polka folio is an idealized contrast to the reality of hard work and urban development present in the region and in the history of the dance itself. It shows the development of American sensibilities during the mid-19th Century surrounding nature, industry, and imported culture from Europe.

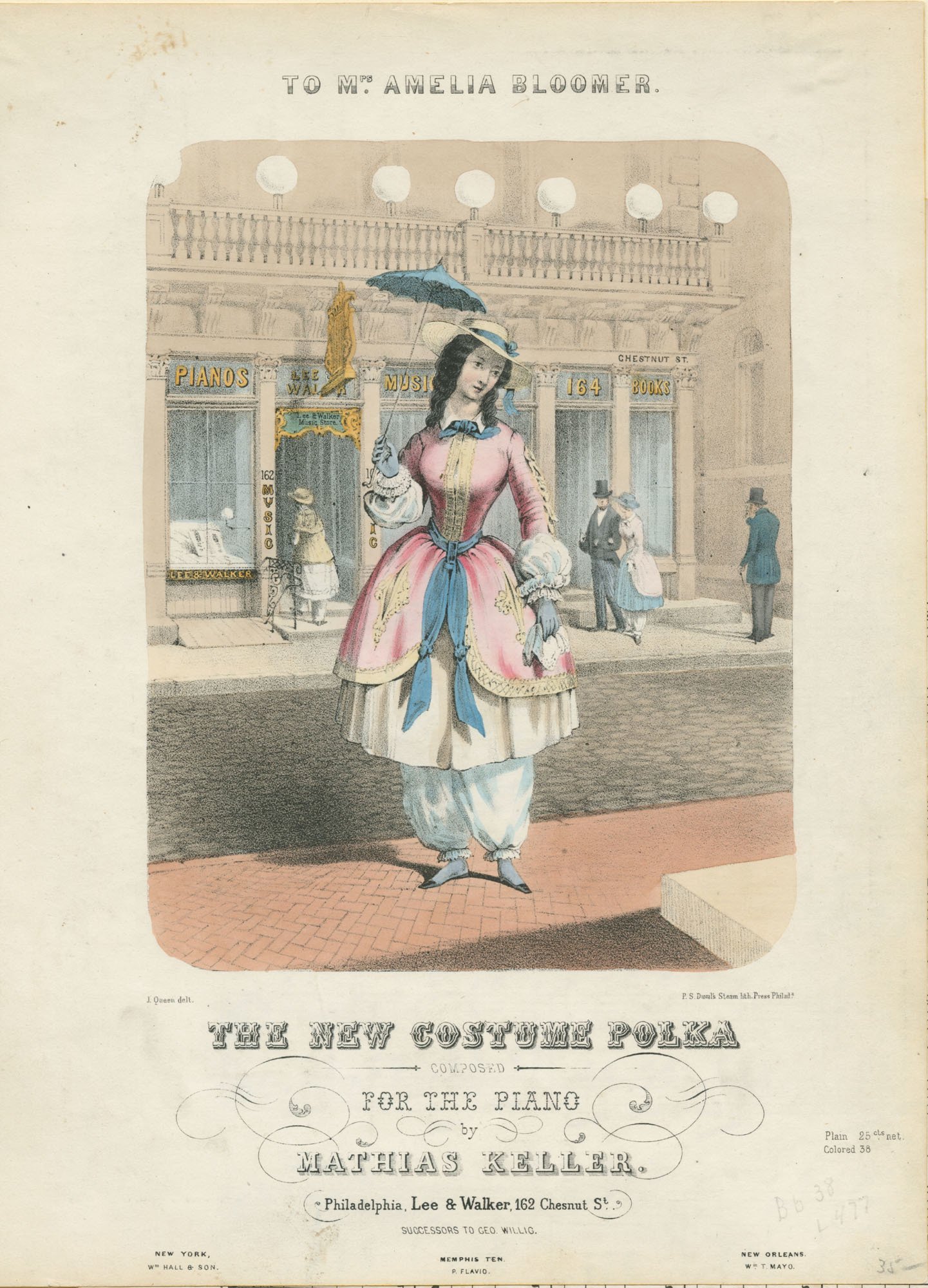

THE NEW COSTUME POLKA

Not all polka music covers depicted natural scenes—and why would they? By this point, the musical style had become somewhat divested from its humble origins. By the fall of 1845, local belles were wearing fashionable polka dots and polka jackets and the city’s dance teachers were vying with each other in advertisements to teach the dance in the “latest, most elegant and brilliant style as danced in the best circles in Paris and London.” (The Philadelphia Dance History Journal, Dance and the Urban Landscape in the 19th Century) Fashionable Philadelphians would have picked up copies of pieces like this The new costume polka composed for the piano by Mathias Keller, to be played at their local dance halls during the winter social seasons. (Image reproduced from The Library Company of Philadelphia)

THE LEDGER POLKA

Perhaps this is why other examples from this era in Philadelphia focus less on community countryside living and more on social landmarks of the city. The Ledger Polka from 1849 shows the Public Ledger Building at the SW corner of 3rd and Chestnut Streets. The Ledger had begun publishing in 1836, as the city’s first penny paper. The street corner in the image is crowded with top-hatted Philadelphia gentlemen eager to read the latest headlines. One lad stands amusingly on tiptoe to read over someone’s shoulder. The last home of the Ledger, built in 1921 on the SW corner of 6th and Chestnut Streets, is still standing. (Image reproduced from The Library Company of Philadelphia)

THE ARCH STREET POLKA

And the Arch Street Theatre Polka, from 1861, shows a vignette of a building with perhaps an even more intriguing history—The venerable Arch St. Theatre, designed by William Strickland, opened in 1828. Mrs. John (Louisa Lane) Drew, to whom this musical composition is dedicated, took over the management in 1861 and ran it as one of the nation’s leading stock companies for three decades. Louisa Lane Drew was the grandmother of the three Barrymores, Lionel, John and Ethel and the great-great-grandmother of Actress Drew Barrymore. John Wilkes Booth was perhaps the Arch St. Theatre’s most infamous company member. (Image reproduced from The Library Company of Philadelphia via The Philadelphia Dance History Journal, Dance and the Urban Landscape in the 19th Century)

THE CITY MUSEUM POLKA

Both of these copies of sheet music, as well as the Wissahickon Polka, sought to identify some cultural marker to the savvy Philadelphian during the mid-19th century. More than just a way to pass down music, the folio was a visualization of the social dynamic of the dance hall and an evocation of urban space. Another example is the cover illustration of the City Museum polka, showing the fancifully adorned City Museum originally built as a church in 1823 at 415-417 Callowhill Street. Several individuals, including families, gentlemen, and a small dog enter, process, and stand in front of the building. (Image reproduced from The Library Company of Philadelphia)

Podcast: An Deep Dive into The Wissahickon Polka, Including a History of the Region

This accompanying podcast reiterates some of the content and allows you to hear some of the music referenced being performed!.

Marie Latham

Art History / 2024

Marie Latham is a first year MA student in Art History concentrating in Arts Management. Combining her research interests of site-specific art and her career in graphic design and arts education, she hopes to work in museum interpretation, designing engaging materials to help visitors to experience art in new ways. She currently acts as an art instructor at Merion Mercy Academy and as a freelance graphic designer. Marie received her BA in Art History with minors in Digital Marketing, Italian, and Economics from The University of Notre Dame. She lives by the Wissahickon and loves exploring it with her dog!