Black Girlhood and White Sight in the Archive

by Megan Voeller

During the Art and Archival Memory seminar, I worked with the selection of photographs shown here—all of which are held in the collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia—as part of my research on contemporary artists whose work appropriates and re-signifies racist imagery from photographic archives. As an art historian in training, I’m interested in how artists today fuse 20th century practices of institutional critique and photographic appropriation in their attempts to heal, or otherwise redress, the structural harm that archives may perpetuate as stewards of such images.

My archival research focused specifically on images of African American girls made by photographers the 1890s. The LCP collection had three photographs that met my limiting criteria—two made by White makers, one by an anonymous maker. The collection also included multiple graphic objects, from playing cards to an advertisement for coach varnish, which featured overtly derogatory caricatures of Black children intended to be legible to a White audience as humorous. In contrast, the photographs I found were more subtle but still evidenced an implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) racist vantage point of ‘White sight’ in apprehending Black girlhood as a subject of curiosity, not care.

As 21st century viewers, how can we relate to such images in ways other than re-invoking or inscribing the intentions of their creators? As scholar Tina Campt asks, “How do we contend with images intended not to figure Black subjects, but to delineate instead differential or degraded forms of personhood or subjection?” Campt proposes what she terms “listening to images” as “a method of recalibrating...photographs as quiet, quotidian practices that give us access to the affective registers through which these images enunciate alternate accounts of their subjects.”

References: Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), pg. 3-5.

Please note: The following artwork may contain images that are not suitable for all audiences. The images contain language that may be offensive or traumatizing to some viewers and may be inappropriate for persons under 18. The displayed pieces reflect the viewpoint of the credited artist(s) and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of Temple University.

LABEL

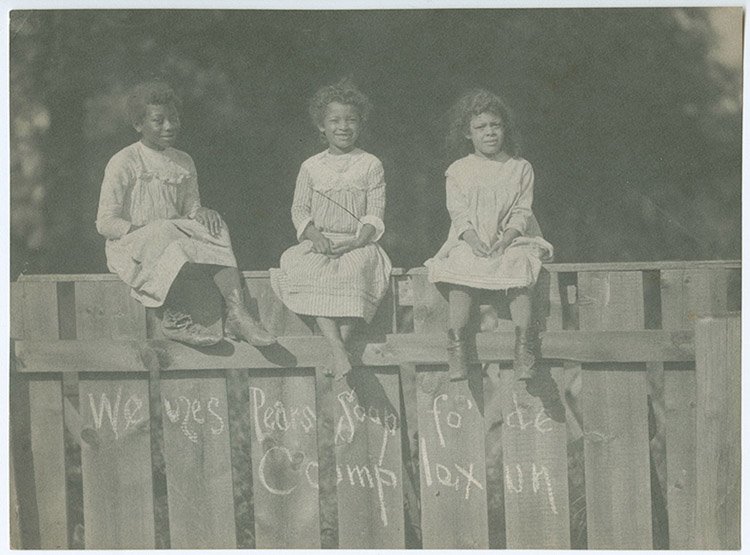

Artist George Bacon Wood, Jr., (1832-1909) was born in Philadelphia into a prominent Quaker family and was largely self-taught as an artist, though he completed some training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. At PAFA, Wood exhibited his work in annual exhibitions nearly every year between 1858 and 1887, becoming known in the region for his oil paintings of natural landscapes and genre scenes, which are held today in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, as well as PAFA. When dry plate photography became widely available around 1880, vastly expanding the accessibility and portability of the medium, Wood took up photography with enthusiasm. Among his frequent subjects were genre scenes depicting the everyday life of African Americans. In this 1886 platinum print of three young girls, Wood captures the playmates sitting on a wooden picket fence on a sunny summer day.

COUNTERLABEL

The identities of the three young African American girls in this late 19th century photograph are unknown, leaving present-day viewers with more questions than answers. The girls, who are perhaps between five and seven-years old, wear lightweight dresses without coats on what appears to be a sunny summer or late spring day in a semi-rural locale. Despite scant contextual information, the emotions of the girls remain vividly apparent in this richly detailed platinum print. The center girl, who is barefoot, grins as if delighted with the adventure of having her picture made. In contrast, the girl on the right side of the photograph looks less at ease, even uncomfortable and slightly worried. The third girl, on the left, has the most complex expression of all—a combination of wry suspicion directed at the person toward whom she is looking (i.e., the photographer) and her assertion of her own mischievous agency.

The image shown above is an altered version of Wood’s photograph (ca. 1886), shown unaltered at right. In re-presenting it here, I made two choices intended to support ‘listening to the image.’ First, I edited the image so that viewers could encounter the girls without the overlay of Wood’s racist graffiti (described below). Second, I wrote the object’s label/counter-label with exaggerated contrast between a version that blithely centers Wood’s authorship and one anchored in the girls’ experience. In the original image, the photographer—or perhaps an assistant—has handwritten a chalk inscription on the picket fence below the girls’ small legs. In oversized lettering suggestive of a commercial sign, the fence reads “We uses Pears soap fo’ de complexun.” It’s a phrase that echoes a late 19th century advertisement for the British Company Pears Soap, which conflated cleanliness with racial superiority and depicted non-Whiteness as a deficiency correctable by soap.

When I saw this photograph in the LCP archives, what really stuck with me was the emotion on the third girl’s face. How did she feel about the person taking her photograph? Would she have been able to read the chalk inscription? Why did she and her companions choose to sit on the fence? Was it a novel experience they couldn’t resist, despite a gut feeling of mistrust? Wood’s gambit was to create a photograph that functioned as a racist joke within the context of “White sight,” theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff’s term for “a set of assumptions, concepts, infrastructures, learned experiences, symbols, and techniques that form a screen by which a person makes white reality.” But the girls he was looking at were also looking back. What did they see?

Work cited: Nicholas Mirzoeff, White Sight: Visual Politics and Practices of Whiteness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2023), pg. viii.

The other two images I found at LCP shared something that I didn’t understand at first—both incorporated the word “study” into their titles. In her book Study in Black and White, art historian Tanya Sheehan analyzes the prevalence of racial humor in late 19th and early 20th century photography as a reflection of “white Americans’ wished-for social superiority in the face of black emancipation, waves of immigration, and further efforts to bring ‘others’ into the national body.” Her book’s title derives from the frequent use of the term ‘a study’ in racist images, including a stereocard depicting African American babies nestled in cotton, published by the Universal Photo Art company of Philadelphia in 1900. The image shown here—“A study in chocolate,” a lantern slide ca. 1900—was made by an unidentified member of the Columbia Photographic Society, a Philadelphia group active from 1889 to 1953.

Like “A study in chocolate,” the photogravure “A Brown study” (ca. 1890) invites viewers to regard Black girlhood with a distant curiosity. Does that frame of reference make these images racist? If so, how should they be described or made available for access through archives? I was especially interested in “A Brown study” as a work attributed to a female photographer, Helen P. Gatch (1861-1942), an Oregon-based artist who exhibited and published her work nationally at the turn of the 20th century. Whereas individual intention seems less ambiguous in the case of Wood, the question of what the makers of these two images intended remains more open. Perhaps that openness also leaves ajar more possibilities for how such pictures can be interpreted and understood by future viewers.

Work cited: Tanya Sheehan, Study in Black and White: Photography, Race, Humor (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018), pg. 3.

Megan Voeller

Art History / PhD

Megan Voeller (they/she) is a current PhD student in Art History at Tyler School of Art & Architecture. They are a Philadelphia-based educator, curator and writer whose work explores critical intersections of art and health. Megan’s art historical research focuses on contemporary artists who work across photography/media, institutional critique and socially engaged art to illuminate and transform connections between the body, identity, health, politics and power.